Consider the Role of the Trusted Advisor

By Wayne A. Neu, PhD, Gabriel R. Gonzalez, PhD, and Michael W. Pass, PhD

*The full research article will appear in a future issue of Industrial Marketing Management. Individual agents with whom clients interface are often the most critical vehicle for developing and maintaining high-performing buyer-seller relationships (Palmatier 2008). Some firms are enhancing relationship performance by expanding the roles of client contact personnel (e.g., agents, sales people, etc.) to that of a trusted advisor. The practice is emerging in a variety of industries including accounting, information technology, and finance (Kahan 2005; Quinley 2005). In this article, we summarize our recent research on the trusted advisor (TA) by first explaining the distinct role of a trusted advisor and the key relationship traits that enable one to perform that role. We then discuss relationship behaviors of the TA and how they lead to improved decision-making quality for the client. We close with a summary of relationship behaviors on behalf of the client that create value for the TA and their firm, and highlight when TAs matter most.

The Distinct Role of a Trusted Advisor

A TA's distinct role is to help a client reduce uncertainty surrounding decisions for which the client is responsible. The underlying motivation for such a role stems from the recognition that those who make decisions need to gather and process information to cope with uncertainty and enhance the quality of their decisions (Galbraith 1973). Decision makers typically have two mechanisms to cope with uncertainty and increased information needs: 1) develop buffers to reduce the effects of uncertainty (e.g., award an agent a trial contract for a home listing so the seller can see the marketing support/traffic generated among potential buyers) and 2) develop information processing capabilities to enhance the flow of information and thereby reduce uncertainty (Premkumar, Ramamurthy, and Sanders 2005). Given the resource constraints with which most clients are now faced, they often find it difficult to dedicate the resources needed to develop such capabilities and meet their information needs. A TA has the ability to help satisfy this need and thus help improve the client's decision-making quality. The extent to which a client relies upon and uses information provided by a TA depends largely on perceived trustworthiness (Parayitam and Dooley 2009).

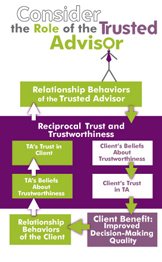

Key TA-Client Relationship Traits: Reciprocal Trust and Trustworthiness

At the core of an agent's ability to perform the role of a TA is a high degree of reciprocal trust and trustworthiness (Serva, Fuller, and Mayer 2005) formed with the client. Trust can be defined as the willingness of one party (e.g., client) to be vulnerable to the actions of another party (e.g., agent) (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman's 1995). While the willingness to be vulnerable implies risk taking, trust is not an observable risk-taking behavior. Instead, trust is a psychological state that can lead to risk-taking behaviors. In addition, trustworthiness is the main driver of trust (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman 1995). Therefore, reciprocal trust in a TA-client relationship is the kind of trust that forms when both parties observe behaviors of each other, form their beliefs about the other's trustworthiness, and then reconsider future behaviors based on those beliefs (Serva, Fuller, and Mayer 2005). In the following sections we explain the key relationship behaviors of the TA and the client that drive beliefs about trustworthiness and, at the same time, are driven by trust.

Relationship Behaviors of a Trusted Advisor

Information quality. Our research indicates that TAs are adept at providing the client with high quality information. The quality of information can be judged on several attributes (Nicolaou and McKnight 2006) of which seven emerged during our study. Three attributes characterize the information shared--relevance, bias, and completeness, and four attributes characterize the process through which it is shared--proactiveness, timeliness, frequency, and responsiveness. A TA provides information that is highly relevant, meaning it is applicable to the client and useful in his/her decision-making (Bailey and Pearson 1983; Wang and Strong 1996). For example, during our study one client emphasized how his/her TA "really stick[s] to the nitty-gritty" while an account manager who is considered a TA explained, "You want to definitely share information. You want to say 'Hey, I heard about this. I think it's very important.' I don't think that you do it unless you're 100% sure that it's going to be a great value to [the client]." A TA also provides unbiased information that is perceived by the client as objective and impartial (Wang and Strong 1996). TAs value doing what is in the best interest of the client and this general orientation was indicated to a high degree by sharing unbiased information that is genuinely intended to help clients improve the effectiveness of their decisions. The third attribute of the information shared is that of completeness, or degree to which information is of sufficient breadth and depth for the client's decision-making (Wang and Strong 1996). Most important to the client is the TA's complete up-to-date understanding of developments in a range of factors relevant to the client's decisions, and advice in the form of viable alternatives to consider when making those decisions. For example, as a client couple considers the supply of homes on the market while "shopping" for a new home, the pair's criteria and priorities can clearly change in the shopping process. Thus, a TA is focused on updating his/her understanding of the decision criteria through the shopping process. Importantly, the four attributes shaping the perceived quality of information are characterized by the information-sharing process. First, a TA provides information proactively by developing an in-depth understanding of the client's information needs and fulfilling those needs through formal and informal collection and processing of information. Second, TAs are timely with information, and by timely we refer to the gap between when something that is relevant to the client occurs and when the client is informed of the occurrence. So, if a particular house of interest to a buyer enters into a contract for purchase, a TA knows to inform his/her client immediately so the client's consideration set can be immediately updated. Third, TAs provides information to their clients more frequently than those who are not considered TAs. Frequency is important because each time a TA shares information, there is an opportunity to shape the client's beliefs about trustworthiness. As such, one who frequently shares information simply has more chances to shape those beliefs. Finally, TAs are responsive and by responsiveness we refer to the time between a customer's request for and the TA's delivery of information. High quality decision support network. Our research also indicates that a TA forms a high quality network of people to support the client's decision making, and the TA's network is characterized by four key attributes. That is, a TA is highly prominent in his/her network and maintains what is referred to as centrality. Basically, a TA establishes and maintains a central bridging position in the flow of resources between members of his/her network and the client. In addition, a TA's decision support network is highly diverse and includes ties to a range of individuals within his/her own firm and extends to a broad collection of individuals outside of the firm. If a needed resource is not available from within the firm, a TA "makes up the deficiency," as one individual in our study stated, and activates the right resource from outside the firm. Perhaps most importantly, members of a TA's decision support network are highly relevant or useful to the client's decision making. When a client needs information that extends beyond the TA's ability to provide it, a TA quickly and accurately locates the right resource to satisfy the need. Finally, a TA's decision support network consists of a large number of direct ties, meaning s/he accesses many of the network members without going through intermediaries (Knoke and Yang 2008). In essence, a TA knows where the right resource is and has direct ties to the resource enabling the TA to quickly match the client to the resource or facilitate the flow of needed information.

Client Benefit: Improved Decision-Making Quality

Decision-making quality can be judged in terms of the outcome of a decision and the process through which it is made (Dean and Sharfman 1996). Client trust in their TA manifests itself as a reliance on the TA for information activities in the decision-making process. Basically, TAs become what Aggarwal and Mazumdar (2008) refer to as a surrogate for the client when they assume, in part, the activities of gathering and processing information and activating other people in their network who are relevant to the client's decisions. By enhancing the quality of the client's decision-making process, a TA improves the effectiveness of decisions made by the client. A TA thus helps drive decision outcomes that can lead to benefits for the individual client (e.g., reducing costs and effectively responding to environmental developments).

Relationship Behaviors of the Client

Upon forming strong positive beliefs about a TA's trustworthiness and realizing improved decision-making quality, clients tend to engage in four key behaviors that indicate their trust. These behaviors create value for TAs and their firms. Specifically, clients who participated in our study are among the most loyal in the TA's portfolio of clients, and their loyalty is to the individual TA rather than the TA's firm. In addition, clients tend to award their TA's firm a high share of the client's business. We define share of business as the percentage of an individual client's total purchase requirements for all products that the TA's firm could supply (Anderson and Narus 2003, p. 43). All of the clients who participated in our study awarded their TA's firm a share of business that is at or nearly 100%. Another common relationship behavior exhibited by the client is referring the TA to other decision makers. In general, partners are proactive and put forth a high degree of effort or, as one individual explained, "really go to bat" to create ties between the TA and other potential clients. Finally, a partner's trust in their TA manifests itself in reciprocity of information quality, and the reciprocity occurs on the same seven aforementioned attributes that characterize the information and the process through which it is shared.

When Trusted Advisors Matter Most

Given the potential value of a TA-client relationship, should all agents become Trusted Advisors? Our research shows that developing into a TA has the greatest potential value when clients experience a high degree of uncertainty in their decision making. Uncertainty arises from two key factors, the first of which is complexity of decisions made. Complexity is defined as the heterogeneity and range of factors that are relevant to a decision (Dess and Beard 1984). Complexity increases uncertainty since more factors need to be considered when making a decision. In our study we consistently heard clients describe decisions for which they are responsible to be highly complex and subject to a range of interrelated factors. One of the participating TAs emphasized the issue by explaining, "If they weren't dealing with a complex system or complex network or complex whatever, they wouldn't need me." The second key factor that contributes to uncertainty is the extent to which the environment is dynamic (Dess and Beard 1984). A dynamic environment is one in which changes occur to factors relevant to the decision(s), and changes can vary in frequency, magnitude, or predictability. Thus, a dynamic environment increases uncertainty since decisions need to be made more frequently with less predictability than when decisions are made in a stable environment. We believe that real estate professionals are working with clients undertaking complex decisions in a dynamic environment. Thus, the opportunity to become a Trusted Advisor to your clients is yours.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References

Anderson, J.C. and J.A. Narus (2003), "Selectively Pursuing More of Your Customer's Business," Sloan Management Review, 44 (3), 42-49. Aggarwal, P. and T. Mazumdar (2008), "Decision Delegation: A Conceptualization and Empirical Investigation," Psychology and Marketing, 25 (1), 71-93. Bailey, J.E. and S.W. Pearson (1983), "Development of a Tool for Measuring and Analyzing Computer User Satisfaction," Management Science, 29 (5), 530-545. Dean, J.W. Jr. and M.P. Sharfman (1996), "Does Decision Process Matter? A Study of Strategic Decision-Making Effectiveness," Academy of Management Journal, 39 (2), 368-396. Dess, G.D. and D.W. Beard (1984), "Dimensions of Organizational Task Environments," Administrative Science Quarterly, 29 (1), 52-73. Galbraith, J. R. (1973). Designing Complex Organizations. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Kahan, S. (2005), "Working with the Trusted Advisor," Partnerships, December, 4-5. Knoke, D. and S. Yang (2008), Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Mayer, R.C., J.H. Davis, and D.F. Schoorman (1995), "An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust," Academy of Management Review, 20 (3), 709-734. Nicolaou, A.I. and D.H. McKnight (2006), "Perceived Information Quality in Data Exchanges: Effects on Risk, Trust, and Intention to Use," Information Systems Research, 17 (4), 332-351. Palmatier, R.W. (2008), Relationship Marketing. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. Parayitam, S., and R.S. Dooley (2009), "The Interplay between Cognitive- and Affective-Conflict and Cognition- and Affect-Based Trust in Influencing Decision Outcomes," Journal of Business Research, 62 (8), 789-796. Premkumar, G., K. Ramamurthy, and C.S. Sanders (2005), "Information Processing View of Organizations: An Exploratory Examination of Fit in the Context of Interorganizational Relationships," Journal of Management Information Systems, 22 (1), 257-294. Quinley, K.M. (2005), "Filling the 'Trusted Advisor Role," Insurance Advocate, 116 (17), 22-24. Serva, M.A., M.A. Fuller, and R.C. Mayer (2005), "The Reciprocal Nature of Trust: A Longitudinal Study of Interacting Teams," Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26 (6), 625-648. Wang, R.W. and D.M. Strong (1996), "Beyond Accuracy: What Data Quality Means to Data Consumers," Journal of Management Information Systems, 12 (4), 5-33.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

About The Authors

Wayne A. Neu, PhD

Assistant Professor of Marketing, California State University San Marcos

Wayne is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at California State University San Marcos where he teaches courses in services marketing, research, and advertising. Neu's research focuses on relationship marketing and new service formation and he has published in the Journal of Service Research and the International Journal of Service Industry Management. Prior to joining CSUSM, Wayne held positions at the Metropolitan State College of Denver and at Cornell University. His professional history also includes nine years as a principal for a consulting firm. There, Neu provided consulting services and developed and delivered seminars for diverse audiences from several leading U.S. and multi-national firms including Ford Motor Company (Germany, Canada, and the U.S.), General Motors, and Samsung (South Korea). Wayne earned his PhD from the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University.

Gabriel R. Gonzalez, PhD

Clinical Associate Professor of Marketing, Arizona State University

Gabriel Gonzalez is a Clinical Associate Professor of Marketing at Arizona State University. Gabriel conducts his research in the area of relationship marketing and personal selling, and his recent research focuses on the role of social networks in the formation and maintenance of customer relationships by inter-firm boundary spanners. He is also interested in exploring the ability of sales organizations to recover from sales failures and respond to customer service complaints more effectively. His research has been published in the Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Journal of Services Marketing, Journal of Advertising Research, Journal of Health Communication, and other scholarly publications. He has taught various courses at both the undergraduate and graduate level including Personal Selling and Sales Management, Fundamentals of Marketing, Strategic Marketing, and Customer Relationship Management. He is a key member of Arizona State University's Personal Selling and Relationship Management Initiative which provides undergraduate students with the education and training to enter the sales profession, and develops strong relational bonds between the university and selling organizations in the community.

Michael W. Pass, PhD

Associate Professor of Marketing, Sam Houston State University

Michael W. Pass is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Sam Houston State University and holds a PhD from the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. He has practitioner experience from positions including Director of Sales and Marketing, Area Marketing Manager and National Accounts Manager with firms including Morrison Restaurants, Inc., Burger King Corporation, and Edwards Baking Company. Prior to joining Sam Houston State University, he was with California State University San Marcos where he held a Biggs Harley-Davidson Senior Experience Professorship. Michael teaches courses related to personal selling, sales management and the marketing of services and regularly presents on topics related to these research interests. Michael is published in journals such as the Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice and the Journal of Financial Services Marketing.